We live in a debt-based economic system.

There is over $100 trillion of debt in the United States supported by just (!) $21 trillion of dollars.

There is not enough money to pay back all that debt!

If you're wondering how that is even possible — you are not alone.

The entire system is based on a simple but important idea that has to do with how banks operate.

I’m sure you noticed that it doesn't cost anything to open a deposit or a checking account — it’s free! Not only it’s free but banks even pay you interest on your funds!

“Well, that’s how it’s always been!”

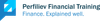

Indeed, we take it for granted now but take a moment to stop and think about it. Like any other company, banks have operational costs — employees, rent, fees, suppliers, etc.

They sure aren't using their own funds to do that. Wall Street is not a charity.

So where does the revenue come from?

The Old Banking Model:

Long, long ago, in a galaxy far away, banks charged customers to open an account. In other words, you had to pay the bank to convince them to take your money! I know, what a crazy world!

But back in those days, banks relied more on direct fees for income. Customers' deposits were also backed up by gold that was kept in the banks' vaults.

Over time, however, banks noticed that not all depositors needed access to all their money at the same time and some of the funds could be lent out to someone else.

The bank received interest on those loans which it used to cover various operational costs. Eventually, competition forced banks to remove customer fees altogether and prompted them to share the interest income with depositors.

Fractional Banking: What Is It and How It Works?

So what's the big deal with banks lending money and earning interest? Especially since it allows them to offer essential banking services for free.

The issue is that banks now use your money to earn a profit for themselves! (wait, my money? Yes, your money!)

If you thought you were just giving money to banks for safekeeping — you're not. The truth is that you are lending your funds, with the implied promise that you can always get it back.

So when you see that number in your online bank account, that money is not actually there!

Most likely it's sitting in somebody else's mortgage.

And here's the crazy part!

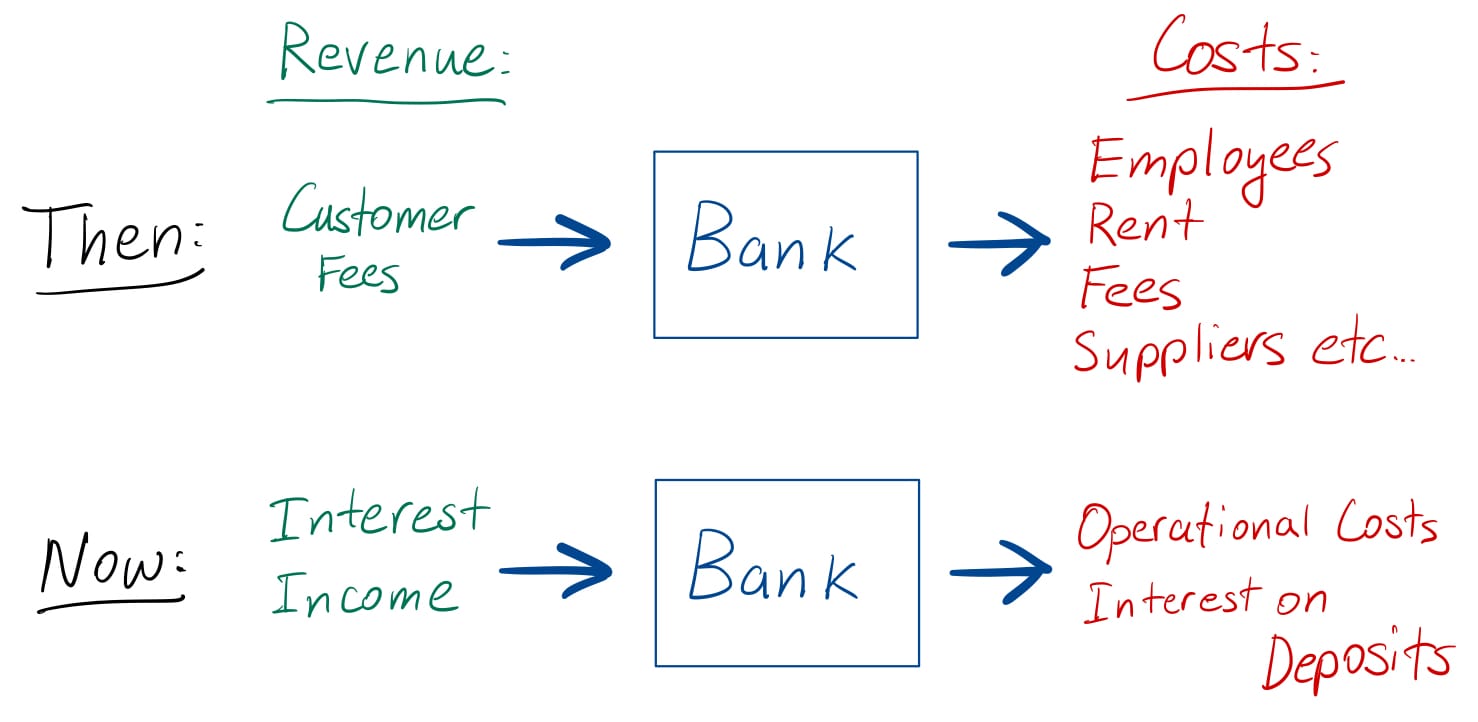

Suppose you deposited $100 into your bank.

What happens when the bank lends your money to someone else?

You still think you have your money, right?

But the borrower also has that money! (wait, my money? Yes, your money!)

They can deposit it into their bank account and now there are $200 of deposits in the system, even though we started with just $100!

But, hey, why stop there, right? The lender's bank can lend out the same $100 again (and again) increasing the amount of money in circulation and effectively creating new money! Whoosh! Money printing in action.

Reserve Requirement:

You can probably see a problem here already.

What if one of the depositors decides to spend some of their money? Since the bank lent it all out, it doesn't have the funds to make the payment and needs to recall the loan back, which is often difficult to do.

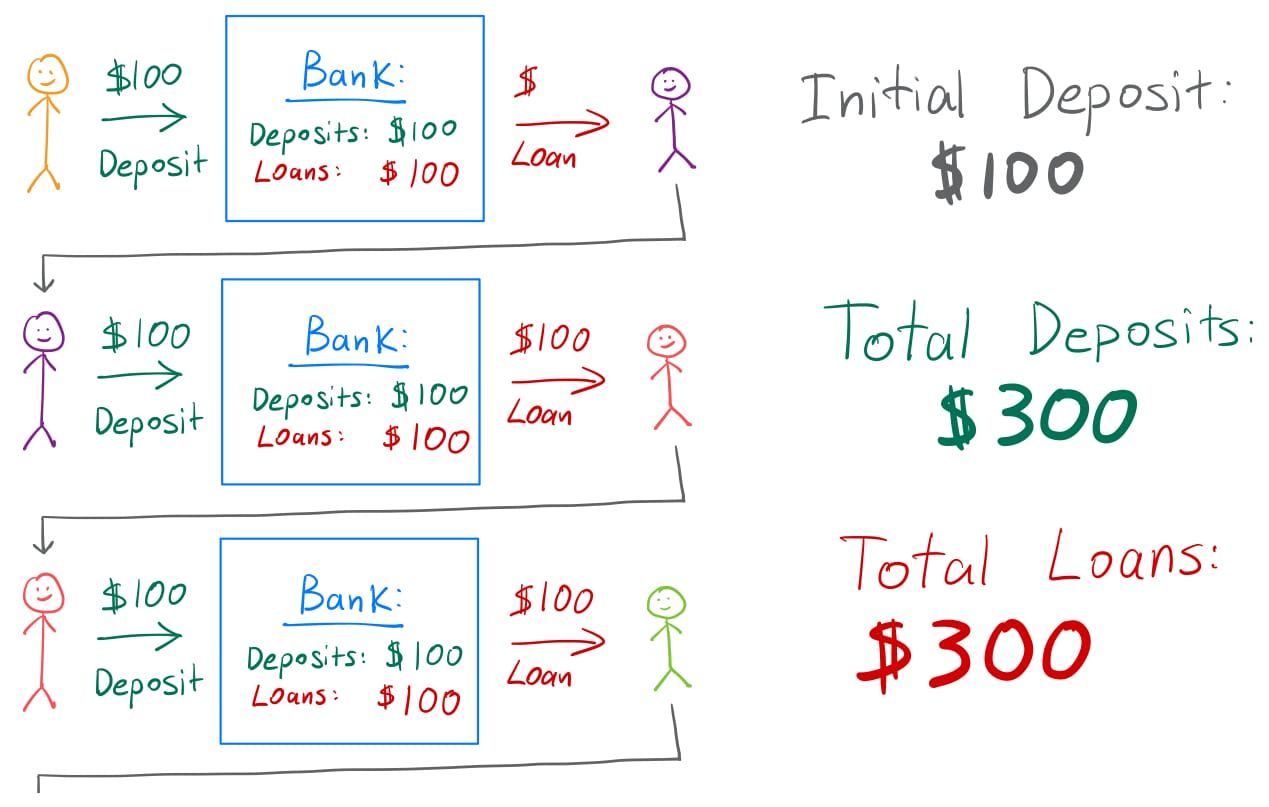

To avoid situations like these, banks don't lend out all of their deposits, but only a fraction of them (hence the name "fractional banking"). The rest is kept as cash on their balance sheet.

This cash is called reserves, which you can think of as the banks' money. Banks use it to settle transactions and meet customers' withdrawals.

How much of the customers' deposits a bank needs to hold as reserves is determined by a reserve requirement.

For example, a reserve requirement of 10% means that banks need to hold 10% of deposits on their books. Every time a bank lends out a deposit to someone else, it keeps 10% as cash and lends the remaining 90%.

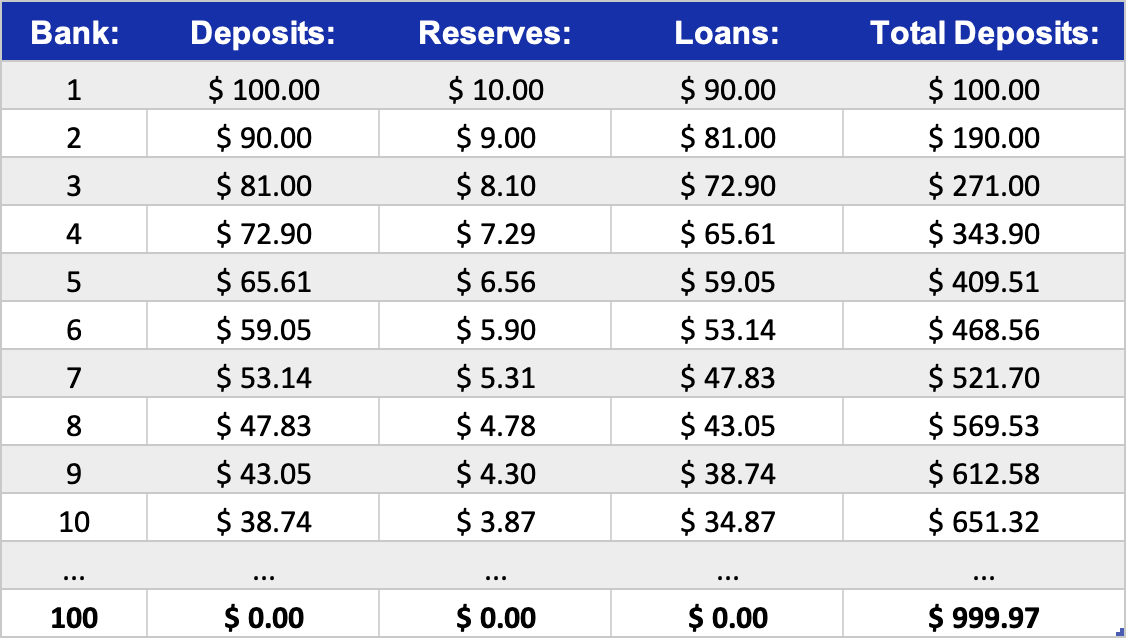

Using an example of $100, the bank has to keep $10 as reserves and can lend out the remaining $90, which becomes a deposit in another bank, like in the process earlier.

This other bank now keeps $9 as reserves and lends out $81 which again becomes a deposit in another bank.

As long as there's demand for loans (very important!), this process can continue indefinitely, until there's no money left to lend out. This can be seen in the table below.

Money Multiplier and Credit Expansion:

You can see that starting with just $100, there is now $1,000 in circulation! Mind-blowing, I know!

This is possible through the magic of credit creation — i.e. lending and borrowing.

Every time a bank extends a loan, it creates new money in the economy. Loans create deposits.

The original $100 was "multiplied" into more money.

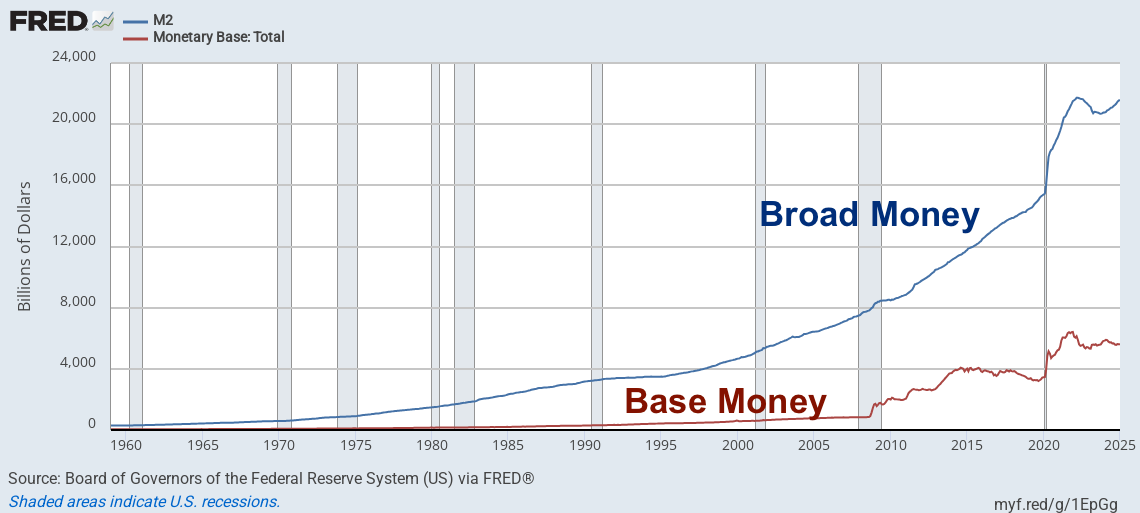

The initial money in the system is known as base money, whereas the total final amount is called broad money, which mostly consists of deposits and physical cash.

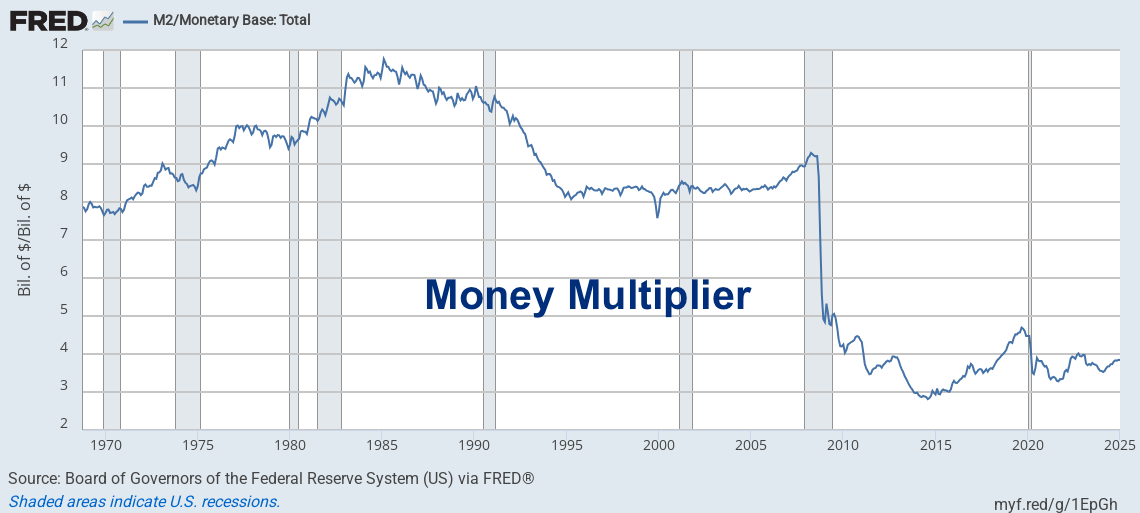

The ratio between the two is called the money multiplier and it shows how much money the banks created in the process of credit expansion.

Real-Life Example:

In the chart below you can see an example of the above concepts for the United States.

Red line is base money and there's about $5.6 trillion of that. Banks multiplied it into the blue line, which shows there's about $21.5 trillion of broad money.

The ratio between the two is the money multiplier, which sits at about four right now:

Historically money multiplier has been much higher than where it is now — it sort of fell off a cliff following the 2008 financial crisis. This was a result of regulatory changes that required banks to keep much more reserves than before — i.e. "ample reserve environment".

Hence, banks now are much better capitalized and have more cash backing up all those deposits — i.e. more base money compared to broad money.

Two Major Implications of the Fractional Reserve System:

1. Monetary Policy:

Since banks create loans in response to demand for borrowing, this demand depends on how expensive taking out a loan is — i.e. interest rates.

If rates are high, consumers and corporations are discouraged from borrowing, which leads to fewer loans and less money being created by banks and vice versa.

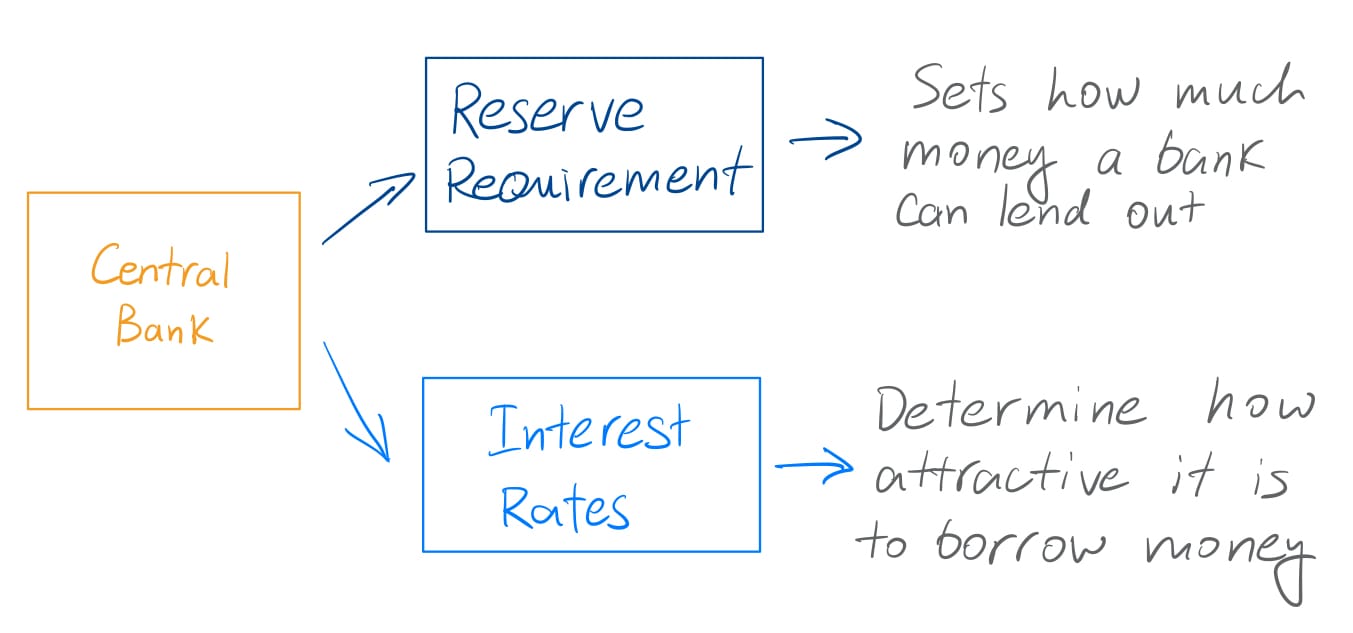

Hence, fractional banking allows central banks to control the amount of money in circulation (and hence inflation) by changing the reserve requirement and setting interest rates.

Currently, the reserve requirements are fairly low and it's the interest rates that act as a primary lever to control credit expansion and inflation.

2. Stability (Fragility) of the Financial System:

Fractional banking makes the economic system fragile.

You probably noticed the big elephant in the room: banks don't have enough capital to back up all the deposits.

But we all believe they do!

This illusion is supported by a bank's promise that you can withdraw your funds at any moment. And if you can — it must be there. And if the promise holds for all the depositors, it would imply all the money is there.

But it's not! Smoke and mirrors.

Only a small fraction is there. Just enough to support this illusion. Just enough to prove to those willing to test the system that their funds are there.

Everything else? Gone. Not there. It was given away as mortgage loans. As business loans. As credit card debt. And the rest was used to buy financial products, like government and corporate bonds (economically the same as lending money).

Bank Liquidity and Solvency Crises:

So if everyone wants their money back at the same time — guess what? The illusion falls apart. The king is naked. The bank will fail to meet the withdrawals unless they unwind the whole chain of loans and investments, which would be impossible to do (and catastrophic for the economy).

This is known as the liquidity crisis. Banks simply don't have enough cash to pay all the depositors asking for their money.

It doesn't mean they're insolvent, no. They got assets — they got these loans and bonds and whatnot. It's just that many of these products are illiquid. Banks can't sell them instantly and get their money back. So what do they do?

Collapse? Whoa, whoa, not yet. Wait a second. Banks simply need a bit of financing to meet the deposit demand.

They can borrow some funds from other banks. They can raise some capital in the capital markets. They can also sell some of their assets, like corporate and government bonds, crashing the market along the way. If all else fails, they can call their friends at the Fed and ask for some of that sweet liquidity.

In this tug of war, the depositors can win. If there's a bank run and everyone wants their money back, the bank can become insolvent and collapse. This happens if a bank's assets (loans, investments etc) fall below their liabilities, which is mostly deposits.

Hence a liquidity crisis can evolve into a solvency crisis, if not taken care of.

Case in point — 2008. Within the fractional banking system, banks took too much risk, had very little cash and reserves, became overleveraged, and didn't know what to do when:

- Depositors asked for their money back.

- The value of their assets collapsed as the mortgages started to default left and right.

- There was no one to borrow funds from as other banks were in the same boat.

A liquidity crisis turned into a solvency crisis.

What's the #1 THING to remember?

The entire economic and financial system is designed around fractional banking.

Your money is only partially backed up by cash, while the rest is backed up by loans, mortgages, and various financial assets.

This allows banks to earn interest and offer depositors free banking services.

In the process of extending loans, banks create money. This usually leads to economic growth, as credit can be easily created and invested to innovate, produce more stuff, and employ more people.

However, it comes at the expense of a more fragile economic system as banks need to manage liquidity and solvency risks.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this! I sincerely hope you found it interesting and valuable.

Please let me know if there are any specific topics you'd like to learn more about.